_small.jpg)

_small.jpg) |

|

Update: Make sure to checkout the new Familiar Stranger

mobile phone application:

Jabberwocky

|

INTRODUCTION |

|

|

As humans we live and interact across a wildly diverse set of physical spaces. We each formulate our own personal meaning of place using a myriad of observable cues such as public-private, large-small, daytime-nighttime, loud-quiet, and crowded-empty. Unsurprisingly, it is the people with which we share such spaces that dominate our perception of place. Sometimes these people are friends, family and colleagues. More often, and particularly in public urban spaces we inhabit, the individuals who affect us are ones that we repeatedly observe and yet do not directly interact with – our Familiar Strangers. This research project explores our often ignored yet real relationships with Familiar Strangers. We describe several experiments and studies that lead to a design for a personal, body-worn, wireless device that extends the Familiar Stranger relationship while respecting the delicate, yet important, constraints of our feelings and relationships with strangers in public places. |

|

HISTORY AND DEFINITION |

|

|

The Familiar Stranger is a social phenomenon first addressed by the psychologist Stanley Milgram in his 1972 essay on the subject. Familiar Strangers are individuals that we regularly observe but do not interact with. By definition a Familiar Stranger (1) must be observed, (2) repeatedly, and (3) without any interaction. The claim is that the relationship we have with these Familiar Strangers is indeed a real relationship in which both parties agree to mutually ignore each other, without any implications of hostility. A good example is a person that one sees on the subway every morning. If that person fails to appear, we notice. Familiar Strangers form a border zone between people we know and the completely unknown strangers we encounter once and never see again. While we are bound to the people we know by a circle of social reciprocity, no such bond exists between us and complete strangers. Familiar Strangers buffer the middle ground between these two relationships. Because we encounter them regularly in familiar settings, they establish our connection to individual places. |

|

WIRELESS TECHNOLOGY AND SOCIAL RE-APPROPRIATION |

|

|

While today’s mobile communication tools readily connect us to friends and known acquaintances, we lack mobile devices to explore and play with our subtle, yet important, connections to strangers and the unknown – especially the Familiar Strangers whom we regularly see. Will these systems provide a new lens to visualize and navigate our urban spaces? How will these systems provide an interface to strangers and unknown urban settings? What will such devices look like? How will we interact with them? What will they reveal about ourselves and strangers? Will they alter our perception of place? Of the strange and unknown? Current trends in mobile phone usage increasingly divide people from co-located strangers within their community. Uncomfortable in strange situations or public places, people reach for their mobile phones, dramatically decreasing the chance of interacting with individuals outside of their social groups. We hope that our exploration of the Familiar Stranger will promote discussion around tools that work to improve community solidarity and sense of belonging in urban spaces. Encouragingly, newly emerging mobile phone uses draw us into acceptable social contact with strangers. Flash and Smart Mobs repurpose our existing personal wireless mobile technology to create impromptu social gathering between strangers. |

|

WHAT THIS PROJECT IS NOT |

|

|

While there are hints of Marshal McLuhan’s global village meme within our approach, we are more acutely aware of William Mitchell’s concern for the preservation of the public sphere, entreating that technological enhancements to the urban landscape should improve everyday life while respecting humanity. To that end it is necessary to declare that we are not interested in designing a friend finder, matchmaking device, or system that explicitly attempts to convert our strangers into our friends. Strangers are strangers exactly because they are not our friends, and any such system should respect that boundary. Having strangers on our urban landscape is not a negative thing. On the contrary, the very essence of individual and community health of urban spaces intrinsically depends on the existence of strangers. Their complete removal would almost certainly be detrimental. |

|

STUDY #1: MILGRAM REVISITED |

|

|

Our initial experiment’s primarily goals were to:

Anecdotally, it was obvious that the Familiar Stranger relationship still existed. However, it was unclear to what degree the phenomenon was operating in typical public urban settings, especially in light of the widespread adoption of wireless mobile phones and other electronic devices that did not exist during the initial 1972 study. We updated Milgram’s experiment to see whether his observations were still applicable. |

|

|

|

|

Activities and areas involved in our urban study for Constitution Plaza

|

|

|

|

|

Six page questionnaire used in Study #1: Milgram Revisited

|

|

|

|

|

Sample of a completed survey page from Study #1: Milgram Revisited |

|

STUDY #2: URBAN WALKING TOUR |

|

|

Observations from the Milgram Revisited study suggested a relationship between recognition of strangers and experience of place. To situate our investigation of a mobile application within the real context of potential users, we interviewed nine Bay Area residents on a walk through Berkeley’s business district to address four issues:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DESIGNS |

|

|

Our previous formal studies and anecdotal observations guided a design for a personal, wearable, wireless device that would capture and extend the essence of the Familiar Stranger relationship. These devices can either be attached to fixed objects, such as a bus stop platform, or carried/worn by individuals. Each device is wireless and emits a short range (20m) radio beacon with a random but unique identifier. The wireless transceiver on the device allows each to be able to detect and record all of the other nearby beaconing devices. As two people approach one another, each device transparently detects and records the others unique ID. Over time each device accumulates a log of unique entries of people that have been previously encountered. There is no central server that stores, manages, or processes the data. The logs are unique and stored only on each individual device. Using this data there are several previously identified social factors that can be extracted and displayed. |

|

|

|

|

The Familiar Stranger hardware prototype is based on the MicaDot2 Mote, a 23mm diameter wireless embedded processor. Motes are the design predecessors to Smart Dust and operate using low power and short wireless connectivity, a perfect match to the Familiar Stranger design constraints of detecting nearby people and places. |

|

|

|

|

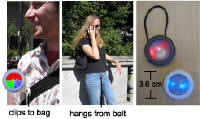

The device needed to support easy viewing access for checking its status. Unlike mobile phones carried in pockets and bags, the Familiar Stranger device design took on several externally displayed form factors such as a belt clip, watchband slip-on, bracelet, and book bag clip. The obvious tradeoff for ease of access is the semi-public display of the device’s status as commented on by users in the Urban Walking Tour study. |

|

|

|

|

The major interface challenge was representing and interacting with complex social data on very small, low-resolution displays. It was also important to visualize the freshness of the real-time data and the passage of time. Finally, we avoided the look and feel of a tracking device by displaying Familiar Strangers collectively rather than as individuals. One of several interface designs we are working with is a diffused circular lens divided into three color regions (red, green, and blue) with two corresponding selection buttons (blue and green). Using an array of concentric LED rings a user can see the degree of familiarity of a place. The red region renders the general state of familiarity by turning on LEDs corresponding to the amount of Familiar Strangers that you have passed who have also frequented the current location (solid LED) as well as the number currently nearby (pulsing LED). This provides a sense of history and freshness of data within a single display. Not all Familiar Strangers are equivalent. Typically, a few have meaning attached to a particular place such as a bus stop, street corner, or club. Others may be ones in your own neighborhood. While the red area depicts the general state of familiarity, the blue and green are for specific personal groupings. Users’ categorize the Familiar Strangers nearby by selecting the green (or blue) button. Later, when members of these groups are re-encountered, their presence will contribute to illuminating both the red (general familiarity) and green (or blue) personalized grouping. |

|

SCENARIOS |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

VIDEO |

|

|

|

|

PAPER |

|

|

|

|

NEXT STEPS |

|

|

We are exploring several different design prototypes and planning for a small deployment of > 50 devices within an urban community setting. Updates will appear on this webpage. |

|

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS |

|

|

Many people provided valuable

insights, feedback, and assisted in various parts of this research

project. We'd like to thanks several individuals below:

|

![]()

Some links take you outside the Intel Research network of

laboratories web site. Other names and brands may be claimed as the property of

others.

|

Legal Information and Privacy Policy © 2002 Intel Corporation |