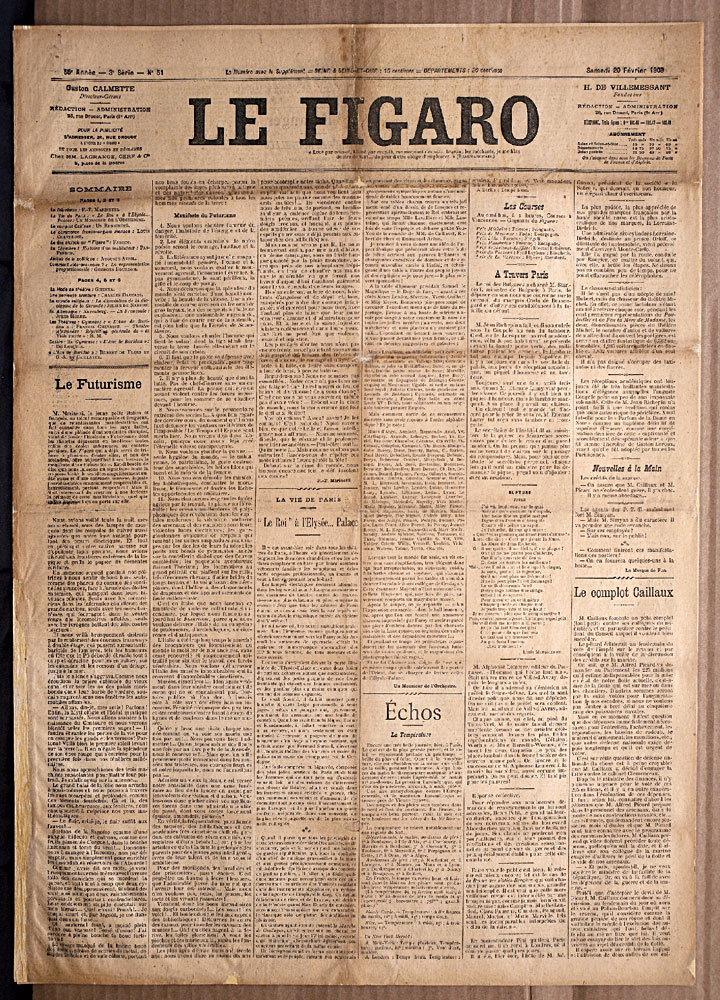

Manifesto of Open Disruption and Participation

Eric Paulos

20 February 2009

on the 100 year anniversary of the publishing of the Futurist Manifesto

Ubiquitous technology is with us and is indeed allowing us to communicate, buy, sell, connect, and do miraculous things. However, it is time for this technology to empower us to go beyond finding friends, chatting with colleagues, locating hip bars, and buying music.

While we should celebrate our success at delivering many vital aspects of Mark Weiser’s original vision of ubiquitous computing, we should also question the scope of this progress. Step back for a moment. What really matters? Everyday life spans a wide range of emotions and experiences – from moments of productivity and efficiency to play, reflection, and curiosity. But our research and designs in ubiquitous computing do not typically reflect this important life balance. The research we undertake and the applications we build often employ technology primarily for improving tasks and solving problems. While these are indeed noble and important areas of research that we must undertake, we claim that the successful ubiquitous computing tools, the onse we really desire to cohabitate with, will be those that incorporate the full range of life experiences. We want our tools to sing of not just productivity but of our love of curiosity, the joy of wonderment, and the freshness of the unknown.

We are at an important technological inflection point. Most of our technological systems have been designed and built by professionally trained experts (i.e. us – computer scientists, engineers, and designers) for use in specific domains and to solve explicit problems. Artifacts often called “user manuals” traditionally prescribed the appropriate usage of these tools and implied an acceptable etiquette for interaction and experience. A fringe group of individuals usually labeled “hackers” or “nerds” have challenged this producer-consumer model of technology by hacking novel hardware and software features to “improve” our research and products while a similar creative group of technicians called “artists” have re-directed the techniques, tools, and tenets of accepted technological usage away from their typical manifestations in practicality and product. Over time the technological artifacts of these fringe groups and the support for their rhetoric have gained them a foothold into computing culture and eroded the established power discontinuities within the practice of computing. We now expect our computing tools to be driven by an architecture of open participation and democracy that encourages users to add value to their tools and applications as they use them. We have seen the “Web 2.0” phenomenon embrace an approach to generating and distributing web content characterized by open communication, decentralization of authority, freedom to share and re-use, and “the market as a conversation”. Similarly, the bar for enabling the design of novel ubiquitous computing systems and “hardware remixes” have been falling to the point that many non-experts and novices are readily embracing and creating fascinating and ingenious ubiquitous computing artifacts outside of the official and traditionally sanctioned academic research communities.

But how have we as “expert” practitioners been influencing this discussion? By constructing a practice around the design and development of technology for task based and problem solving applications, we have unintentionally established such work as the status quo for the human computing experience. We have failed in our duty to open up alternate forums for technology to express itself and touch our lives beyond productivity and efficiency. Blinded by our quest for “smart technologies” we have forgotten to contemplate the design of technologies to inspire us to be smarter, more curious, and more inquisitive. We owe it to ourselves to rethink the impact we desire to have on this historic moment in computing culture.

We must choose to participate in and perhaps lead a dialogue that heralds an expansive new acceptable practice of designing to enable participation by experts and non-experts alike. We are in the milieu of the rise of the “expert amateur”.

We must change our mantra: “not usability but usefulness and relevancy to our world, its citizens, and our environment”

We must design for the world and what matters.

This means discussing ubiquitous computing alongside new keywords such as the economy, the environment, activism, poverty, famine, homlessness, literacy, religion, and politics.

How do we design computing tools to support grassroots activism?

How do we design ubiquitous technologies to effect real political and social change?

We have the power to create an entirely new form of citizen volunteerism, community involvement, and participation. We need to think big impact – outside of our immediate world of academic ubiquitous computing.

In 1961, President Kennedy’s challenge was to “commit ourselves to achieving the goal of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth." Who participated in achieving this goal? – the brave engineers and scientists of the day.

What is our challenge today? Perhaps it is climate change, our environment, or our economy? In any case, the same cultural practice instilled in our ubiquitous computing technology – characterized by open communication, decentralization of authority, freedom to share, and public participation, will be central to our problem solving effort. And who will be the primary leaders in helping to solve these challenges ahead – not the scientists and engineers as in generations past, not us as ubiquitous computing researchers but – “everyone”, you, me, all of us as everyday citizens of our world.

This is our urgent calling. We need to help design the technologies here and now to enable this…to enable us all to participate in changing our world.

Let us choose to make a difference!